“Out of 55 participants with eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, 41.8 per cent felt that social media perpetuated their illness, with greater use correlating to increased severity,” says Dr Victor Kwok, Private Space Medical. This is based on a research study he conducted when he was in Singapore General Hospital.

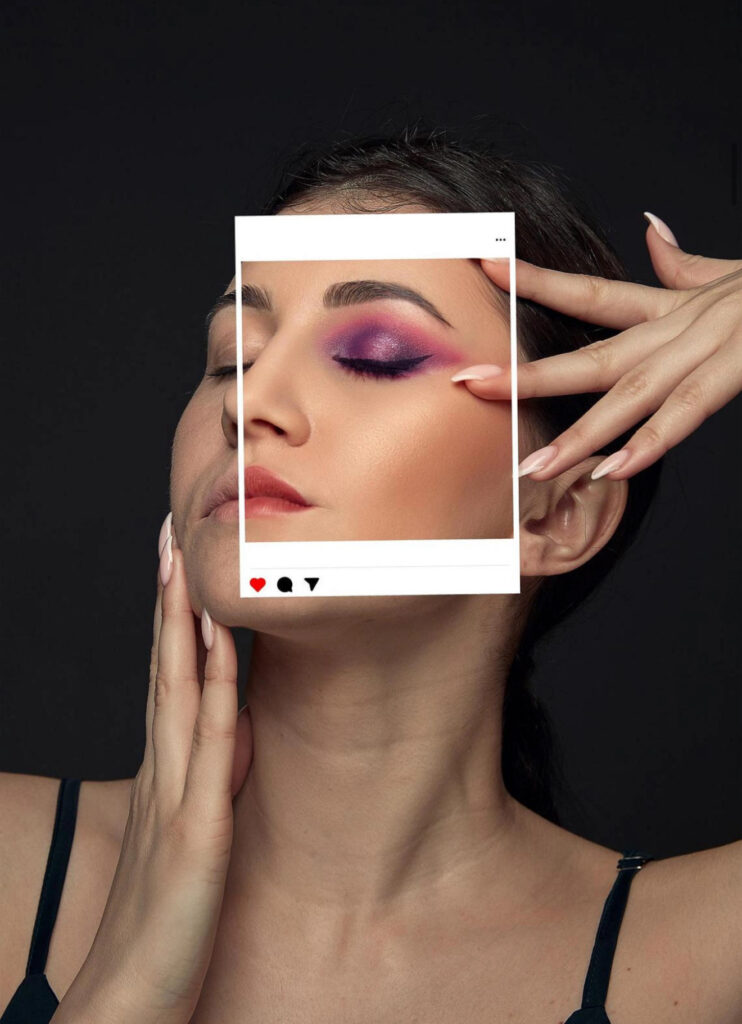

SINGAPORE – Social media selfies may finally be losing their digital gloss as governments and platforms decide it is time for a reality check.

In 2024, Australia gained attention with its proposal to prohibit beauty filters for users under the age of 18, to address negative impacts on teens’ body image. Later that year, the government escalated its stance by unveiling plans to ban social media for those under age 16 entirely, citing concerns over its effects on young people’s mental health.

Big Tech now has a one-year deadline to implement effective age verification measures or face substantial penalties.

In December 2024, TikTok decided it was time to peel back the virtual veneer, announcing a ban on filters that alter physical features for users under 18 for the same reason, to take effect in January.

One of the platform’s most controversial ones is reportedly Bold Glamour, which has sparked significant debate over its hyper-realistic effects. Known for its ability to enhance users’ faces with a soft glam make-up look and subtly alter facial features to conform to traditional beauty ideals, Bold Glamour has been used more than 233.5 million times.

Meta also announced that it will progressively begin to remove certain third-party augmented reality (AR) filters created by external developers from its platforms – WhatsApp, Facebook and Instagram – starting in January.

Filters have profoundly shaped the self-image of Singapore-based content creator Myke Motus, 36, who believes their ban is timely.

In June 2024, he boarded a plane to the Philippines for a rhinoplasty.

It was the culmination of years spent using beauty filters and social media tools that allowed him to transform his virtual appearance into an idealised version of himself.

He began experimenting with filters for fun when Snapchat first introduced them in 2015, but his fascination grew with the arrival of AR filters on Instagram in 2018. These filters use face detection technology to map facial features or body shapes and overlay digital effects or distortions, creating the desired look.

“I loved using the contact lens filter because it makes my eyes pop, as well as nose filters that enhance my facial features, making them sharper and more defined,” he says.

It ultimately motivated Mr Motus to pursue a series of aesthetic procedures in Singapore.

In 2024, he took it a step further by undergoing rib rhinoplasty — a procedure that uses cartilage from the patient’s rib to reconstruct the nose — after consulting a plastic surgeon from a Philippines-based medical aesthetic clinic. The treatments were fully sponsored, with the expectation that he would document and share his transformative journey on social media.

While filters have been around since roughly 2015, their popularity exploded during the Covid-19 pandemic, as millions of people stayed home and turned to video calls and virtual interactions.

Mr Motus’ experience highlights a broader narrative about how digital tools, originally designed for fun and creativity, have evolved into a double-edged sword.

Today, these tools are more advanced than ever, offering hyper-realistic effects that blur the line between reality and digital manipulation. With hugely popular photo editing apps such as Israel’s Facetune and China-founded Meitu, social media users can try different hairstyles and make-up looks with just a tap on the screen.

A 2024 report published by London-based science group The Royal Society found that beauty filters do more than just enhance attractiveness – they also make individuals appear more intelligent, trustworthy, sociable and happy. In the study, 2,748 participants assessed images of 462 people, some with beauty filters and others without. The filtered versions were consistently rated more favourably across various characteristics.

The pervasive influence of beauty filters is a growing concern in Singapore as well.

Ms Leona Ziyan, an executive assistant at a leadership development start-up, believes the ban on beauty filters has come too late, as these tools have been embedded in societal beauty standards and digital culture for years.

She has been using them for as long as she can remember.

“I document my life frequently, and it’s unrealistic to look flawless every day, so beauty filters really help with making my appearance more acceptable when filming,” says the 27-year-old, who is also a part-time content creator.

Ms Ziyan knows people who, after years of heavily photoshopping their online images, are now turning to plastic surgery to match their digitally enhanced appearances.

“Their realities are distorted, but I don’t judge them, because I’ve had enhancements done to beautify myself too. I’ve struggled with some self-esteem issues over the years, so… I can really empathise with them. We’re all trapped in this loop in some ways,” she says.

Social media user Sasha Bao, 33, believes beauty filters should not be banned.

“If people who have self-image issues have a problem with the filters, more should be done to educate them. I feel that the onus is on parents, older siblings and life mentors to educate teenagers, Gen Z and Gen Alpha about the dangers of unhealthy beauty standards,” she says.

The investment manager admits she frequently relies on Meitu to add virtual make-up, and Instagram’s built-in filters to smoothen her skin texture. “I used to wear light make-up even for a quick trip to the supermarket, but I decided to let my skin breathe. Now, when I take photos, I use beauty filters to ‘apply’ make-up before posting on Instagram. It’s so convenient.”

Both women acknowledged the impact of filterson their self-esteem.

Ms Bao says: “Beauty filters give me a confidence boost because I look better on the surface. But when I remove them, I can’t help feeling that my real face is a little inadequate.”

She adds that in an effort to embrace the new trend of sharing more authentic Instagram stories, she has started posting selfies without filters. However, she is not ready for social media to go filter-free.

“If there are fewer filters available to users, I will definitely use social media less as it would lack the fun and colour of previous posts which used filters,” she says.

While Ms Ziyan has not done any plastic surgery, she has gone for several aesthetic treatments over the years, including nose thread lifts and botox.

She references the growing “looksmaxxing” trend, which has gained traction especially among younger men on mainstream social media platforms such as TikTok since 2024. The trend centres on maximising one’s physical appearance through subtle enhancements (such as make-up or grooming) and more extreme measures (like cosmetic surgery).

“There are content creators in the US who use artificial intelligence (AI) beauty filters to create enhanced versions of customers and then sell the enhanced picture to them for about $80 a person,” she says, admitting that she has been tempted to buy one.

Dr Victor Kwok, a consultant psychiatrist at local mental health clinic Private Space Medical, notes that social media use exacerbates mental health conditions such as anorexia nervosa and body dysmorphic disorder, particularly among younger individuals.

Referencing a 2016 study he conducted while practising at the Singapore General Hospital, which examined social media use in people with eating disorders, the 46-year-old says: “Out of 55 participants with eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, 41.8 per cent felt that social media perpetuated their illness, with greater use correlating to increased severity.”

Beauty filters amplify unrealistic beauty standards, contributing to issues such as body image dissatisfaction and anxiety, he adds.

“The illusion of perfection – thinness, flawless skin or sharp noses – is unattainable and often subconsciously internalised. This can lead to shame, a drive for thinness and exaggerated concerns about appearance.”

He recalls a case involving his 17-year-old Singaporean patient with anorexia nervosa.

“When I reassured her that it’s okay to have a normal body weight, she’d show me images of slim, fair-skinned influencers she followed. During her clinic visits, she applied make-up to look very fair. I often wondered if she realised that these influencers are using beauty filters,” he says.

According to aesthetics doctor Shauna Tan-Chiam from local aesthetic clinic David Loh Surgery, most beauty filters reinforce pre-existing social biases, often promoting the idea that stereotypically Caucasian features are ideal.

She says: “Beyond the racial biases, it also reinforces the social perception and stereotypes that people with certain physical attributes like clear skin or thin bodies are more intelligent or successful. This may cause users to view variation or deviation from the characteristics applied by the filters as inadequacy, or worse, ugly.”

Dr Tan-Chiam, 30, notes that it is not uncommon for patients to bring filtered images of themselves as references during initialconsultations. While she believes there is no harm in identifying areas for improvement, she emphasises the importance of setting realistic expectations.

“Even with aesthetic or cosmetic procedures, they are unlikely to look exactly like an artificially edited image,” she says. “When care is taken to speak to patients at length, we can often identify underlying concerns such as wanting to look less tired and more refreshed, or wanting to look less angry and more approachable. A realistic and appropriate treatment plan can then be taken to achieve these goals, instead of focusing on a specific physical trait based on a single filtered image.”

Dr Tan-Chiam believes that while individuals should have the autonomy to make informed decisions about their appearance, they should also consider the fleeting nature of beauty trends.

“Filters are often based on temporary preferences,” she says. “Beauty trends are constantly evolving and what may be a preferred look right now may not withstand the test of time. As such, identifying personal values and preferences will be far more beneficial in the long term.”

Dr Kwok supports the ban on beauty filters for underage users, viewing it as a positive step towards a society that embraces diverse body shapes and sizes.

However, Dr Tan-Chiam cautions that these measures alone are not enough to fully address the underlying issues, as damage has already been done in distorting opinions or perceptions of body image.

“My only fear is that there will be new spin-offs, platforms or apps where more filters can be created with fewer controls or regulations. AI-AR technology continues to grow in sophistication and can easily be trained to create more realistic filters,” she says.

In the past year, Ms Ziyan, who used to share only heavily edited photos of herself, has been experimenting with posting less filtered content and embracing vulnerability in her online presence.

“I was spending too much time on filtering and editing photos and videos. And to be honest, the internet doesn’t really take well to heavily edited content any more. TikTok values more real, authentic moments. People are just tired of things that are too filtered, and so am I,” she says.

She adds that she has formed deeper, more authentic connections with her online audience as a result.

“I’ve had more conversations with depth and made more warm relationships showing my ‘unfiltered’ moments than my filtered ones. Sometimes I wonder, did people truly care for the overly filtered images, or was that an unrealistic standard I imposed on myself?” she reflects.

A recent collaboration with American beauty brand Glow Recipe has bolstered her confidence.

“They specifically requested unfiltered images and told me they value ‘realistic depictions of skin’. That made me feel immensely proud to work with a brand aligned with such values,” she says.

“When big brands and corporations take the lead in showing real people, real skin and real bodies, it creates ripples of change in society. This is the cultural movement we need brands to support.”